Homelessness: My Story

Recently I was travelling home on a bus and looked out of the window to see a boy who was in the same care home as me when we were teenagers. He was younger than me, and this is what he had been reduced to: lying inside a sleeping bag, on the side of the road in the capital city of Scotland, the 14th richest country in the world.

Earlier this year, I read an article about a young man who was given a sandwich by a girl leaving Starbucks – despite the staff telling her to ‘let nature take its course’. As I continued reading, the article mentioned that he had experienced the care system. This is not the first time Starbucks has discriminated against the homeless. Last year, they refused to serve a homeless man, ejecting him from the premises, despite him having the funds to purchase a sandwich. This inspired me to write this article and open up about my own experience with homelessness and look at the relationship this has with the care system.

Back in 2002, the Homelessness Task Force report set landmark new standards on the issue. But budget cuts, reductions in social security payments for some of the most vulnerable, and an insufficient supply of social housing, mean that levels of rough sleeping are on the rise across many towns and cities like my own: Edinburgh.

According to The Salvation Army, in 2015 a third of Scots over the age of 18 believe that addiction is the main cause of homelessness and only 3% have stated that they believe it is down to relationship breakdowns. It is a common misconception that homeless people are addicts and that they are using the money gained from begging to feed this addiction. This perception dehumanises people and does not shine light on the real issue, which is that drug users require support, not vilification.

There is another common misconception that homeless people are simply ‘faking it’, using their homeless status as a way to make money, despite having a place to stay and an income. Although it has been proven that this is sometimes true, it takes concern and attention away from people who are genuinely homeless and do not have the stability that others do. Many people beg for hours every day, just so they can get money to rent a room in a B&B or a hostel. For many people, hostels are the only home they have which is a terrifying thought.

Formal statistics by Who Cares? Scotland suggest that at least 21% of care leavers become homeless within five years of leaving care, however this relies on care experienced people declaring their care status, so it’s estimated this figure could potentially sit a lot higher. In reality, there is a whole host of circumstances that can lead to someone declaring themselves as homeless, such as physical/mental health or relationship breakdowns. Homelessness is a massive issue that is known in the public eye that is not yet fully understood. Statistics are valuable, research is insightful, but the only way that society will ever grasp or understand these issues is by listening to real life stories from people who have lived through homelessness.

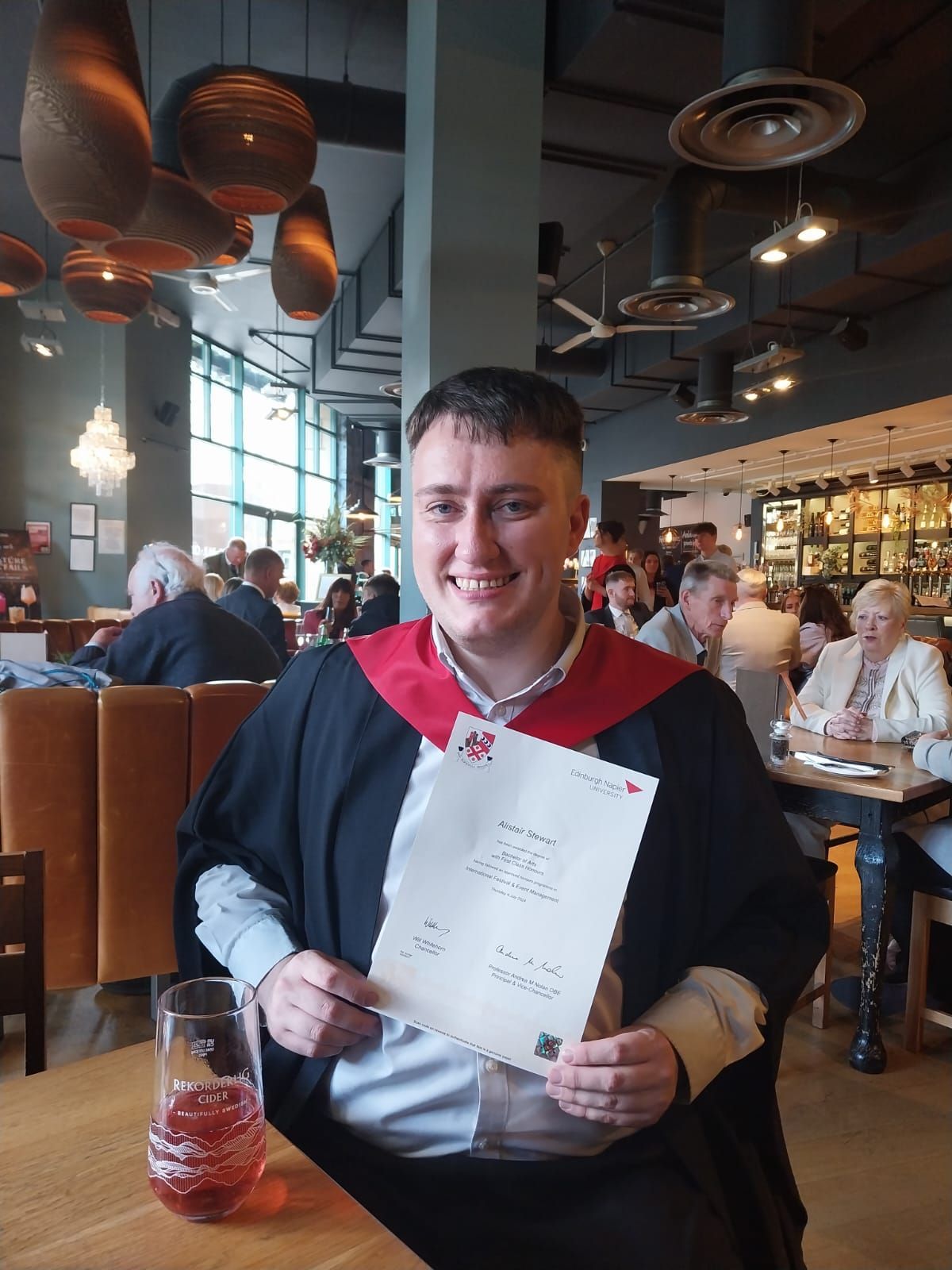

Throughout my life, I have experienced the turmoil, inconsistency and darkness that homelessness contains and have decided to open up about my own experience, as I know how important it is for the homeless and care experienced population to have their voices heard. From a very young age, I was brought up by my grandmother. Just before my sixteenth birthday, she was diagnosed with cancer. My social worker decided that it was within my best interest to go into residential care as neither me nor my gran could cope. My behaviour was out of control and my mental health deteriorated due to a number of factors. Just under a year later, I was moved to a supported tenancy and was given help to secure my own tenancy in the future. At the age of 19, I secured my first council flat. I thought this would be great for me, but I was living in a rough area, miles away from my gran and nothing in the flat worked. On my first night, I laid down newspaper on the floor and sat down, hoping that the loneliness and terror would go away. It never did.

A few months later, I found drugs in the garden. I called the police and they took the drugs away, but within an hour, my door was kicked in and my neighbour had a knife held to my throat. I was terrified. After that, I was moved for my own safety and although I didn’t fit the stereotypes, I was now classed as being homeless. I was moved about to various settings, such as a B&B and a hostel. Sometimes I didn’t even know where I would be sleeping. Being in these environments reminded me of being in residential care. Things would go missing from my room and to this day, my experience of homelessness was one of the most terrifying ordeals that I had ever lived through.

I couldn’t cope with being in the hostel and eventually applied for a private let, but I was not financially stable and did not have parents to help me, as other young people might. I had restarted college four times and had almost as many mental health breakdowns.

Eventually I secured a tenancy with a housing association and managed to re-engage support to become independent again and give me the stability I needed. I returned to college and was able to begin volunteering as a shop assistant at my local Shelter charity shop, where I worked my way up to become a supervisor. This gave me a chance to give back to those who had faced the same difficulties as I had.

I have been involved in many campaigns with organisations such as Who Cares? Scotland and The Rock Trust, I have voiced my opinion on tackling youth homelessness which has now given a platform for the voices of Scotland’s care experienced people and those facing homelessness to be heard.

Every twenty minutes, a household becomes homeless. Tomorrow morning, more than 5,000 children in Scotland will wake up without a home. They don’t have a voice and neither does my friend on the street. So the rest of us need to speak up loud and support the many demands from organisations such as Shelter, that our government should commit to delivering a new National Homelessness Strategy.

FEANTSA (the European Federation of National Organisations working with the Homeless) disclosed that young people account for 27% of Scotland’s homeless applications despite only making up 11% of the population. In Scotland there are 24 named corporate parents, all of which have a legislative duty to act as a parent towards Scotland’s care experienced young people. Since April 2017, The Rock Trust has stated that around 11% of the young people they support have come from a care background.

Recurring themes, such as leaving care too soon, lack of support and inappropriate placements, have caused up to 5% of care experienced young people to become homeless as soon as they leave care, with as many as 35% of the care experienced population presenting as homeless to their local authorities before their 25th birthday.

Another reason so many care experienced young people become homeless, may be down to the fact that they lack the necessary skills to live independently. In my opinion, if schools were to incorporate life skills and budgeting in some capacity, this may decrease the number of young people lacking these essential skills and will benefit from the knowledge of money management when they become independent.

Homelessness is one of the many issues that the care experienced population have faced and are still living through to this day. I want to make society understand that homelessness isn’t always a choice, and in some cases, it is the only option.

It is time to re-forge Scotland’s commitment to tackling homelessness, with a new national strategy building on the last decade of work. We want clear leadership and accountability, and for the action plan to be considered a priority for the Scottish Government. That’s why I feel compelled to speak out because I am one of the lucky ones. Not all of us come out the other end fighting.